Gallery › Heroes Gallery

Heroes of the Human Spirit: Confronting Terror and Indifference

Historians, journalists, and scholars who have reported on and studied mass killings of citizens in their own countries have dubbed the years of the late twentieth century and the first decade of the twenty-first century as the “Age of Genocide.” An estimated 170 million men, women, and children have been murdered by their own governments, the victims of state-sponsored terrorism.

That is why we cherish those few men and women who have looked upon all people as their equals and who have placed their own lives in danger in order to tell the world of inhumanity and great suffering. These heroes have rescued thousands of lives in danger of extinction because it was “the right thing to do.”

Is this willingness to assume such risk part of our fundamental human nature and the opposite side of evil? Why act for good when it is easier and safer to look aside or even to kill for an ideal that is capable of eliminating “other” human beings who may not even be seen as human?

The profiles of the following “heroes of the human spirit” teach us that we can each make a difference.

Teacher and Docent Curriculum Guide/Discussion Sheet

Audio version of introduction read by Jimmy Chang (1:11)

Audio commentary by Bob Barancik and Dr. Abraham Peck (1:44)

What makes an individual a “hero of the human spirit?” Why would anyone want to step forward and decide to perfect an “imperfect” and “unjust” world? What would happen if many of us decided to take such a step?

Jean M. Peck is a writer, editor, and educator who lives in Portland, Maine. She is the author of two books: At the Fire's Center (University of Illinois Press) and, with Abraham Peck, Maine's Jewish Heritage (Arcadia Press). She is an adjunct professor of English at the University of Maine, Augusta.

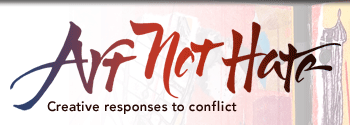

Raoul Wallenberg: Tragic Hero of the Holocaust

Immortalized as a genuine hero, Raoul Wallenberg was one of the most famous men in the history and memory of the Holocaust. He was born in 1912 into a powerful Swedish non-royal family, a family of bankers, diplomats, and politicians. His father died several months before Raoul was born and his grandfather, Gustav Wallenberg, a successful businessman, took responsibility for the young Wallenberg’s academic and professional future.

Instead of banking and business, Wallenberg chose the field of architecture. He traveled to the United States where he received a bachelor’s degree in science from the University of Michigan in 1935. He returned to Sweden hoping to join an architectural firm, but his non-European academic diploma was not seen as a worthy qualification. Therefore, his grandfather sent him to learn both business and banking skills in South Africa and in the British mandate of Palestine in the city of Haifa.

Returning to Sweden in 1937, Wallenberg entered the world of business, equipped with excellent language skills and business contacts. He soon established a partnership with Kolman Lauer, a Hungarian Jew who was the director of a Swedish-based import and export firm specializing in various forms of food and delicacies. That relationship brought Wallenberg to Hungary on several occasions.

During the early 1940s, Raoul Wallenberg visited Hungary many times and saw for himself the growing plight of Hungary’s Jewish community. Germany invaded Hungary on March 19, 1944, and Hitler ordered the deportation of Hungarian Jewry to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

By that time, the Swedish government had completely changed its policies toward Jews seeking a place of refuge. Initially, at the outbreak of World War II, Sweden would not allow Jews to enter, even temporarily. But by 1944, it had reversed its policy and become the first nation to publicly announce that it would accept any Jews who could make their way to Sweden.

In January, 1944, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had finally created an American governmental institution, the War Refugee Board (WRB), committed to saving the few Jewish communities that had not yet been liquidated by the Nazis, primarily those Jews who had been allowed to live in Budapest. By the time the War Refugee Board began to take steps toward the rescue effort, more than 400,000 Hungarian Jews, primarily from areas outside of Budapest, were deported to the death camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau. The operation took place between May 14 and July 18.

The WRB contacted the Budapest Jewish community and asked for individuals who would work with the American agency. They also asked for Swedish representatives to be a part of the committee. One of the Hungarian Jewish members of the group was Kolman Lauer, Raoul Wallenberg’s Hungarian Jewish business partner. Lauer nominated Wallenberg, and he was approved by the Swedish government and appointed secretary at the Swedish legation in Budapest as a cover for his mission to rescue Budapest’s Jewish community.

Wallenberg arrived in Budapest in July and immediately began to design and distribute yellow and blue protective passes carrying the coat of arms of the Three Crowns of Sweden. He eventually was able to distribute over 4,500 of them which meant that those Jews carrying the pass did not have to wear the Jewish yellow star as a badge of identification, thus saving them from deportation.

Wallenberg and his staff of Swedish diplomats continued the rescue efforts. He created “Swedish Houses,” where Jews could seek refuge. Blue and yellow Swedish flags hung in front of these houses, more than 30 of them, and Wallenberg declared them Swedish territory. At least 15,000 Jews were able to reach these “protective” houses.

Soviet forces surrounded Budapest at the end of December 1944. By mid-January they had captured control of the city, arresting Raoul Wallenberg on orders from Moscow. The reasons were never made clear, but the fact that he was working on behalf of the War Refugee Board probably convinced the Soviets that he was an American spy.

From that time until the present, the whereabouts of Raoul Wallenberg have remained a mystery. In 1957, the Soviet Union announced that Wallenberg had died in his prison cell probably of a heart attack and that his body was cremated without an autopsy. Then in October 1989, the Soviet Union invited Wallenberg’s half brother and sister to Moscow and gave them the items that had been seized from him when he was arrested including his diplomatic passport and his address book. They also told his family members that nearly all of Wallenberg’s case files had been destroyed.

Raoul Wallenberg, with help from other Swedish diplomats, prevented the deportation of nearly 20,000 Budapest Jews. He was also able to persuade German authorities not to liquidate the city’s so-called “international Jewish ghetto” and its 70,000 residents who would surely have been massacred by the Nazis as a last-ditch effort to destroy the Jewish community.

Wallenberg’s courage and imagination allowed thousands to survive and live full lives. The tragedy was that he was unable to live a life of his own. He has been made an honorary citizen of several nations including the United States and Israel.

Audio version of introduction read by Jimmy Chang (5:26)

Audio interview with Dr. Abraham Peck (9:51)

Raoul Wallenberg risked his life to rescue the remnants of Hungarian Jewry during the final days of Hitler’s war against the Jews of Europe. As a young man, Wallenberg had few if any Jewish friends. He did, however, have a Jewish business partner who lived in Budapest. That partner recommended Wallenberg to be part of an effort by America’s War Refugee Board, a government organization devoted to saving the remnants of Hungarian Jewry. Why did Wallenberg accept? How did he carry out his mission to save Jewish lives? And why was he arrested by Soviet authorities after the liberation of Budapest, taken to a notorious Moscow prison and never heard from again? Is this the fate that awaits those who leave their comfort zones to say no to human injustice and cruelty?

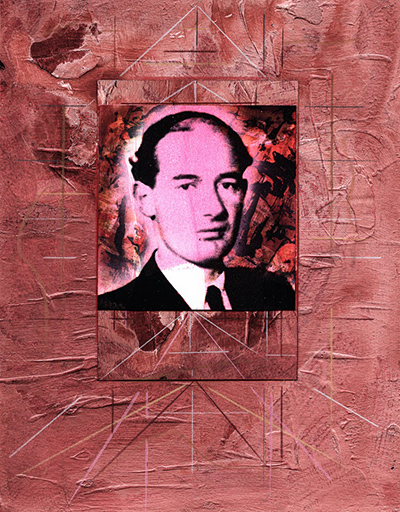

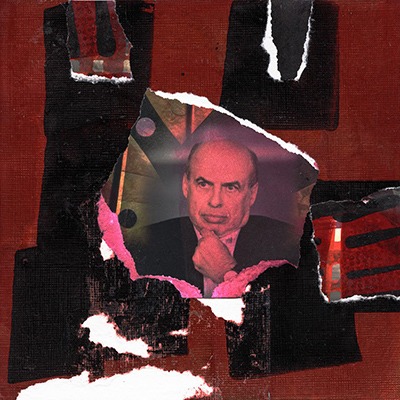

Jan Karski: Messenger of the Holocaust

As a Polish Catholic, Jan Karski, 1914-2000, entered the forbidden world of the Warsaw Ghetto in late August 1942, months after Nazi Germany implemented its plans for the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question,” and saw streets and tenements filled with hungry and dying Jews. He witnessed what he later described as “terrible things.”

As a member of the Polish underground resistance to Nazi occupation, Karski breached the barbed wire gates of the Izbica Ghetto, a Jewish ghetto located near the city of Lublin and a collection point for Polish Jews and other Jews from Czechoslovakia, Germany, and Austria before they were shipped to the death camps of Belzec and Treblinka. He witnessed the murder of dozens of Jews being resettled from local ghettos to Izbica at the hands of brutal Ukrainian guards. Karski (born Jan Kozielewski in Poland’s second largest city, Lodz) was able to see both ghettos, because he was accompanied by members of the Jewish underground who wanted him to see for himself the ongoing destruction of Polish Jewry.

Why he chose to put his life in danger is a complex question. It may have had something to do with Karski’s childhood in a strict Roman Catholic home where religion and acceptance of Jews were important. His mother, a devout Catholic, also adored Marshal Jozef Pilsudski, the benign dictator who ruled Poland during the interwar years and who provided a relatively safe environment for its Jewish community.

But more than anything else, Jan Karski was a Polish patriot who embodied the finest ideals of the nation and the human being. A skilled courier, he was ordered to travel to the nations of the free world to inform them of the plight of Poland and, only incidentally, the plight of its Jewish community.

In November 1942, Karski reached London, the seat of the Polish government-in-exile. After delivering microfilm documents to Polish officials, he scheduled a meeting with the British foreign secretary, Anthony Eden. After telling Eden what he had seen in Warsaw and Izbica, Karski was told by Eden that Great Britain could do no more; it had already done enough by accepting 100,000 refugees.

Karski arrived in Washington in July 1943. He was aware that a few months earlier, in April, the heroic remnants of the Warsaw Ghetto had resisted the Nazi attempt to liquidate those Jews not yet shipped to death camps. For three weeks, before the Uprising was crushed, the Ghetto’s Jews had put up a heroic if impossible struggle. The remaining 56,000 Warsaw Ghetto Jews were taken to the Treblinka death camp.

He arranged a secret meeting with Franklin Delano Roosevelt in which he told the American president that if the Allies did not intervene during the next eighteen months the Jews of Poland would “cease to exist.” Roosevelt replied that Karski was to tell the Polish government “it has a friend in the White House,” but said nothing about the plight of the Jews.

Prior to his meeting with Roosevelt, Karski also met with Felix Frankfurter, a Jewish justice of the American Supreme Court. “Will you tell me about the Jews,” Frankfurter asked. “We have had many reports. What happens to the Jews in your country?”

When Karski reported on what he had seen in the Polish ghettos, Frankfurter rose from his chair and turned away deep in thought. When he faced Karski again, Frankfurter said: “Young man, I am no longer young. Men like me and you must be totally honest. And I am telling you: I do not believe you&ellip;. My mind and my heart are made in such a way that I cannot accept it. No! No! No! I am a judge of men. I know humanity. I know men. It is impossible.”

“Almost every individual was sympathetic to my reports concerning the Jews,” Karski later wrote. “But when I reported to the leaders of governments, they discarded their conscience, their personal feeling.”

Jan Karski remained in the United States as a professor at Georgetown University. He did not seek glory or recognition for his efforts. He lived, rather, with the realization that the world did not care enough about the murder of Poland’s and Europe’s Jews to act in any meaningful way despite evidence of what was taking place.

But world Jewry did care about what Jan Karski had done, even in failure. In 1982 he was recognized by Yad Vashem as a Righteous Among the Nations. In 1994, Professor Karski was awarded honorary citizenship of Israel. At the ceremony he stated: “This is the proudest and most meaningful day in my life. Through the honorary citizenship of the State of Israel, I have reached the spiritual source of my Christian faith. In a way, I also became a part of the Jewish community&ellip; And now I, Jan Karski, by birth Jan Kozielewski&emdash;a Pole, an American, a Catholic&emdash;have also become an Israeli.”

Audio version of introduction read by Jimmy Chang (5:02)

Audio interview with Dr. Abraham Peck (7:28)

Jan Karski was a messenger with a terrible message. As a courier for the anti-Nazi Polish underground and a Polish Catholic, he visited the Warsaw ghetto and a camp that was a collection point for Jews destined for the death camps. He saw the suffering of Polish Jewry and determined that he would take those images to a world that was unaware of the Nazi “final solution.” But what he soon found out was that his message was either ignored or not believed. For the rest of his life, which he spent in the United States, he had to live with the knowledge that his “terrible secret,” the Holocaust, failed to arouse the passions and the actions of an uncaring and unbelieving world.

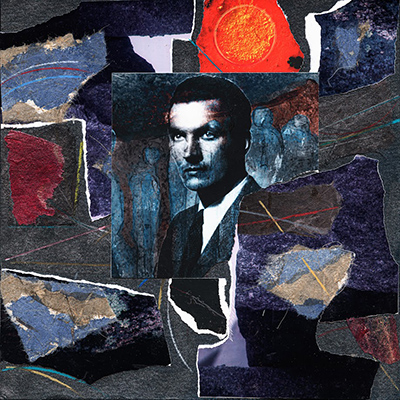

Andrei Sakharov: Physicist and Dissident

Andrei Sakharov achieved both fame and notoriety in his lifetime, first as the inventor of the Soviet atomic bomb, and later as one of Russia’s foremost dissidents and political activists who tried to warn the world about the dangers of the very technology he worked so hard to create.

Born in Moscow in 1921 into an educated family, Sakharov enjoyed spending time with his father in his physics laboratory. Young Andrei was excited to repeat the experiments he saw in the lab, and his parents encouraged him to pursue his fascination with the field.

During World War II, Sakharov worked as an engineer. When the war ended, Russia and America settled into what was called “the Cold War,” where each country, based on mistrust of the other, worked to develop atomic weapons to be used as deterrents to the other country’s possible attacks. Sakharov played a major role in developing these weapons, and became known as the “father of the Soviet atomic bomb.”

During this period of Cold War escalation, Sakharov became more aware of the destructive powers of nuclear weaponry, and began calling for a slow down in the arms race. He wrote an essay in which he spoke of the threat of a world nuclear war if the development of atomic missiles were to continue. The essay was published in several “underground” Soviet journals and circulated widely outside of Russia, but the Russian government ignored the warnings in Sakharov’s essay, and banned him from conducting any kind of military-related research.

This kind of “punishment” for his outspoken views on the horror of nuclear war, only spurred Sakharov on to greater involvement with human rights. His work on these issues led to his nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize and the eventual awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975. However, the Russian government would not allow him to leave the country in order to go to Norway to collect it.

The tighter the grip of the Soviet Union on his freedom, the more Sakharov resolved to work for peace. He was arrested in 1980 because of his protest of the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan and was exiled to a Russian city where foreigners were not allowed to visit. The Russians kept him under tight observation there, and often searched and ransacked his apartment looking for evidence of his contacts with western and progressive scientists who shared his beliefs in the dangers of nuclear weapons. Sakharov was able to call attention to the harassment through essays and papers that were published in western media.

In 1986 he was allowed to return to Moscow under the new policies of perestroika and glasnost, where the Russians allowed more contact and cooperation with the West. For the last three years of his life, he was able to publish his views on peace and human rights without restraint. When Andrei Sakharov died in 1989, he was hailed both inside and outside of Russia, as a man of great integrity and conscience.

Audio version of introduction read by Jimmy Chang (2:53)

Audio interview with Dr. Abraham Peck (4:09)

America’s decades-long cold war against the Soviet Union carried with it the threat of a “hot” war and nuclear destruction. Those scientists, both in the United States and Russia, who carried out experiments with atomic and nuclear power were only too aware that their research contained the implicit and explicit threats of an event capable of destroying our world. Fortunately, some spoke out against their own scientific creations and sought to warn the world of their dangers. Andrei Sakharov, the “father” of the Russian atomic bomb, came to despise the risk that both America and the Soviet Union were taking. He understood that the deterrent of nuclear attack could also become the impetus for an all-out nuclear war. For his courage, Sakharov, and other Soviet citizens who joined him in protest, were treated as mentally unstable, imprisoned and made pariahs within their own communities.

Natan (Anatoly) Sharansky: Saying No to State Terror

Natan Sharansky was born in the Ukraine in 1948. A math prodigy, he was admitted to the prestigious Moscow Physical Technical Institute, despite an enforced quota against Soviet Jews, where he studied mathematics and computer science. At the age of 25, he began his career as a computer scientist at the state-run Oil and Gas Research Institute.

The start of Sharansky’s professional career coincided with a growing sense of Jewish identity and an identification with the State of Israel, a phenomenon among many young Soviet Jews. In 1974, Sharansky, whose family had maintained their Jewish heritage despite efforts to suppress Judaism by Soviet authorities, decided to emigrate to Israel along with his future wife, Natalia Stieglitz.

Natalia’s request for a visa was approved, but Sharansky was denied permission to leave. The Soviet government insisted that he knew too many state secrets from his work at the Oil and Gas Research Institute. On the day before she left for Israel, Natalia married Anatoly. He promised that he would soon join her.

In 1975, the Soviet Union was one of the signers of the Helsinki accords, a set of conditions that not only guaranteed the current borders of all the states of Europe, a condition favorable to the Soviets, but also committed all the signatory nations to “respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief.” This was a clause that the Soviet Union had no intention of honoring.

But the Helsinki Accords allowed a small but influential group of Soviet human rights activists to monitor the article dealing with human rights and freedoms. In 1976, eleven of the activists founded the Moscow Helsinki Watch Group. Among the founders were the Soviet physicist ,“father of the Russian atomic bomb,” and political dissident Andrei Sakharov and a 28-year-old computer programmer named Anatoly Sharansky. Because he was fluent in English, Sharansky soon became the spokesperson for the group. He also became a prime participant in the Refusenik movement, the unofficial term for individuals, typically but not exclusively Soviet Jews, who were denied permission to emigrate abroad. The term refusenik was derived from the "refusal" handed down to a prospective emigrant from the Soviet authorities.

Within two years, Sharansky was declared an enemy of the State and arrested on charges of spying for the United States and for treason. On the day of his sentencing to thirteen years of forced labor in Perm 35, a Siberian Labor camp, he addressed his wife and the Jewish people:

For more than two thousand years the Jewish people, my people, have been dispersed. But wherever they are, wherever Jews are found, every year they have repeated, ‘Next year in Jerusalem.’ Now, when I am further than ever from my people, from Avital [his wife’s Hebrew name] facing many arduous years of imprisonment, I say, turning to my people, my Avital, ‘Next year in Jerusalem.’ Now I turn to you, the court, who were required to confirm a predetermined sentence: To you I have nothing to say.

Sharansky spent the next decade as a prisoner of the Soviet Union under terrible conditions, both in a Moscow prison and in the Siberian gulag, often in solitary confinement and in a special “torture cell.” He survived because of his religious belief, his resistance to despair and emotional surrender, and the promise he made to his wife about their eventual reunion in Israel. During those years, he became a symbol for human rights in general and Soviet Jewry in particular.

Finally, after an international campaign led by his wife to free him, Anatoly Sharansky was released from the gulag as part of an East-West prisoner exchange on a bridge between East and West Germany. He was met by the Israeli ambassador to West Germany who presented him with his new Israeli passport under the name Natan Sharansky.

In the more than two decades that Natan Sharansky has lived in Israel, he has achieved an extraordinary career as a journalist, Soviet Jewish activist, and Israeli government minister. In 1986, the United States Congress granted him the Congressional Gold Medal and in 2006, President George W. Bush awarded Sharansky the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Sharansky

Audio version of introduction read by Jimmy Chang (4:23)

Audio interview with Dr. Abraham Peck (7:15)

Born into a Soviet society, that had made the decision to destroy Judaism as a religion and culture, Anatoly Sharansky was a perfect example of the “new Soviet man.” He was a brilliant mathematician who contributed to the scientific advancements in Soviet technology. But he was also a “secret” Jew, whose family had never lost their sense of “Yiddishkeit,” of Judaism as a civilization and a religion. During the decades of the Soviet Jewish “refuseniks,” those Jews who protested the denial of their right to leave the Soviet Union, Sharansky became a leading voice in that movement. He also joined other scientists like Andrei Sakahrov in voicing objections to nuclear armament. For his efforts, Sharansky was imprisoned and sent into the Soviet gulag system, with its deprivation of essential human needs, its brutal winter weather, and its isolation from the world. But his spirit never broke and his identity as a Jew only increased. When he was finally released and sent to the West in a prisoner exchange, Sharansky made his way to Israel where he became an inspiration for those Jews still trapped in the Soviet system, and a leading political voice for human rights and the survival of the Jewish State.

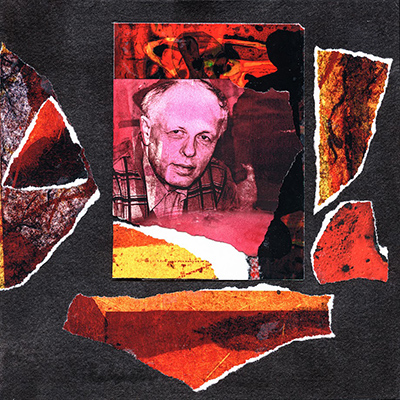

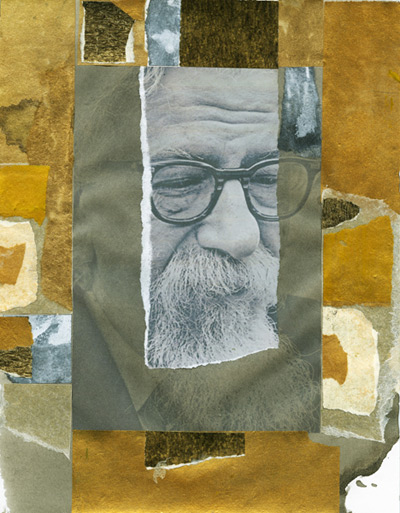

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel: A Passion for Truth

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, 1907-1972, is considered by many as the most significant Jewish theologian of the twentieth century. He is remembered not only as an inspiring teacher and lecturer, but as the author of numerous works dealing with the teachings of the biblical prophets, the relationship of humankind to God, the world of Hassidic Jewry, and tikkun olam, the transformation and healing of the world. Heschel was also a social activist who was indignant at the injustices of society. For him, every deed posed a problem with moral and religious implications.

Born into the world of Eastern European Hasidic Judaism, Heschel could have become the leader of a major Hasidic sect. He broke with family tradition, however, and at the age of twenty, left Poland for Germany where he earned a doctorate in theology and philosophy from the University of Berlin.

The horrors of the Nazi assault against German Jewry forced Heschel to leave Germany and return to Poland. In 1939, he was brought to America as part of a rescue effort coordinated by the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati and joined its faculty for five years before he was appointed Professor of Jewish Ethics and Mysticism at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America in New York where he taught from 1945 until his death in 1972.

Many of Heschel’s family were not as fortunate. They died at the hands of the Nazis.

Yet, in spite of his grief over the horrors of the Holocaust, Heschel asked the Jewish world to reconnect with God. He also challenged Jews and Judaism to awaken from a kind of spiritual deadness in the synagogue and the rote and dreary learning that took place in America’s Jewish rabbinical seminaries of the 1950s and early 1960s. Most of all, he was pained by the relative silence of American Jews in the face of two of the greatest injustices of the twentieth century&emdash;the continuing denial of civil rights for African Americans and the Vietnam War.

Heschel first met the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1963. King encouraged Heschel to involve himself in the Civil Rights movement, and Heschel encouraged King to take a public stand against the war in Vietnam. Both men used the imagery of the Exodus from Egypt as a metaphor for their social activism. Both men walked arm in arm during the historic civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, in March 1965. For Heschel, the march had a spiritual significance: “For many of us,” he wrote, “the march from Selma to Montgomery was about protest and prayer. Legs are not lips and walking is not kneeling. And yet our legs uttered songs. Even without words, our march was worship. I felt my legs were praying.”

Heschel also found the continuation and escalation of the war in Vietnam to be a “moral outrage.” To speak about God, he often said, “and remain silent on Vietnam is blasphemous.” He remained deeply engaged in anti-war efforts during the last years of his life and spoke and taught about the need to end the war in both public speeches and in his classroom.

Finally, he involved himself deeply in interreligious activities between Jews and Christians. In the early 1960s, he influenced the drafting of the historic statement Nostra Aetate (In Our Times) during the Second Vatican Council, a statement that forever changed the relationship between Roman Catholicism and Judaism and, once and for all, removed the charge of deicide, the crucifixion of Jesus, against the Jewish people. He was also the first rabbi to be appointed to the faculty of the Protestant Union Theological Seminary in New York.

His was an extraordinary life. As one scholar has written, “Heschel made his impact by the wholeness of his person, by his passion for social justice, by his scholarship in the Jewish tradition and by his religious thinking on the human condition.”

Abraham Joshua Heschel taught that if we are created in the image of God, each human being should be a reminder of God’s presence. If we engage in acts of violence, murder and the abuse of human and civil rights, we desecrate the divine likeness. And we must not turn away, but act to stop these desecrations of God’s name and God’s role in history: “The opposite of good is not evil,” he wrote, “the opposite of good is indifference. In a free society, some are guilty, but all are responsible.”

Audio version of introduction read by Jimmy Chang (4:24)

Audio interview with Dr. Abraham Peck (5:00)

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel resembled the biblical prophets whose lives he studied and about whom he wrote. Like those prophets, he urged American Jewry to return to the contract formed between God and the Jewish people at Sinai. In order for American Jewry to honor that contract, to become the “light unto the nations” that was the promise of Sinai, Heschel asked that Jews focus on the two major issues tearing the nation apart, namely the crisis of civil rights and the war in Vietnam. With his partner, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Heschel represented the highest ideals of Judaism and of America.

View the Classroom Learning Sheet and Activities | Back to top of page